Wanted: Firefighters, everywhere

BY Kim Harrisberg, Seb Starcevic and Angelina Davydova 17 September 2021

The wildfire had drawn firefighter Grigory Kuksin and his colleagues deep into the Siberian forest before they realised there was no way out.

Cut off by a ring of burning trees, Kuksin told his crew to turn their hoses on each other.

Soaking their uniforms may have saved their lives as they ran through the flames and emerged on the other side, panting and covered in ash.

.gif?language_id=1)

"There are dangerous moments in every blaze," Kuksin, 41, said. "Fighting fires is not about heroism or getting emotional reactions or adrenalin, it's about clear rules and regulations."

Wildfires, fuelled by scorching temperatures, are putting immense additional pressure on firefighters as they obliterate Californian towns and engulf Italian olive groves.

But despite the job's intense demands and dangers, many firefighters work long hours and are poorly paid - if at all.

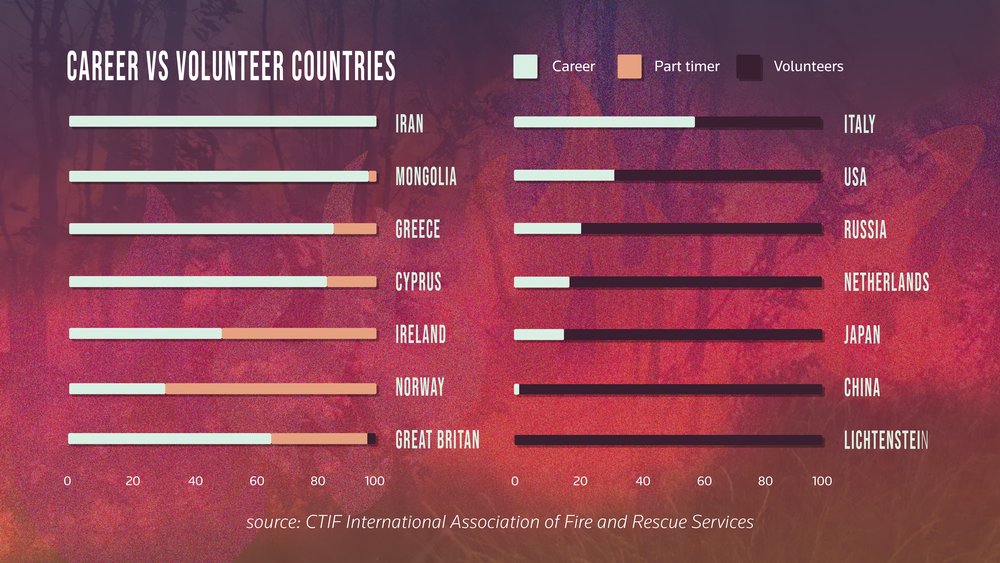

Countries including Australia already enlist unpaid volunteers to bolster overwhelmed fire services. If wildfires become more frequent, ordinary people may increasingly have to help tackle blazes on their doorsteps.

The Thomson Reuters Foundation asked three firefighters, including two volunteers, how their jobs are being affected by climate change.

When battling a blaze with fellow firefighters, South African volunteer Slee Mbhele experiences a rush of adrenalin but something else, too: her country's racial and economic divides seem to dissolve.

She describes fire as "the great equaliser", putting all firefighters on an equal footing, no matter their colour, age or gender, as they work as a team.

"We see inequality all around us but when we fight the fire, we all pull our weight together, we are all the same," said the medical researcher, who has been part of Cape Town's Volunteer Wildfire Services for three years.

South Africa is one of the world's most unequal countries, according to the World Bank, marred by poverty, high levels of crime and corruption nearly 30 years after the end of the white minority apartheid regime in 1994.

Like other cities, Cape Town is visibly divided between the white-dominated suburbs and poor townships, home to most of the country's Black majority.

Mbhele, who began volunteering after witnessing a blaze in 2018, worries that inequality may begin to affect whose homes get burned as wildfires become more frequent.

She fears the fires will move from suburban homes close to the mountains towards Cape Town's crowded informal settlements, which have limited water supplies and narrow roads that are hard for vehicles to access.

"With informal settlements growing closer to vegetation they are more likely to catch on fire - how do we prevent that? We need to think about the materials used to build shacks, materials that are less flammable," said Mbhele.

"Fires are in your face now, other countries are battling blazes, it's on the news ... if you don't know about it, it's because you don't want to know," Mbhele said.

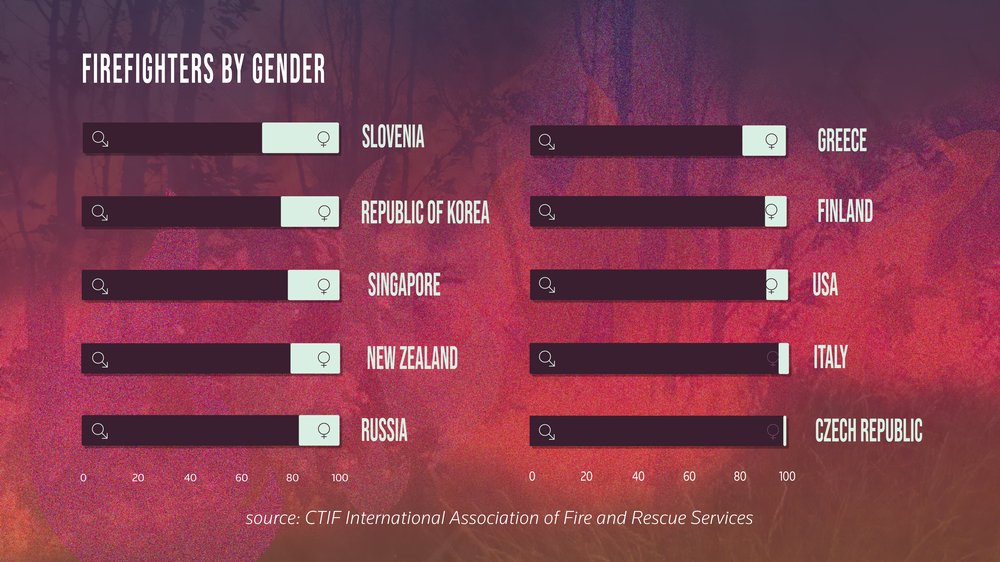

When Mbhele joined the Volunteer Wildfire Services, 70% of the 287 volunteers were men and she was the only Black woman. Still, Mbhele said she was not deterred as she has been pushing boundaries since she was young.

"I didn't realise there would be this obvious racial ratio and I thought I might face discrimination but that wasn't the case ... it doesn't matter who is under the mask and the PPE, I realised that this is my tribe," Mbhele said.

Growing up in KwaDabeka, a semi-rural township in KwaZulu-Natal, she witnessed first-hand the inequality that divides South Africa when her mother pushed to get her into a good school where some classmates made her feel inferior.

"Education is everything," said Mbhele, referring to her own life story, but also to fighting fires and learning more about climate change.

Cape Town regularly experiences fires, often triggered by human behaviour and likely spurred on by climate change, fierce winds and an increase in flammable vegetation, according to researchers from the nearby University of Stellenbosch.

The city was hit in April by one of its worst wildfires in recent memory, which spread across the slopes of Table Mountain to the University of Cape Town, damaging historical sites and libraries and forcing people to evacuate their homes.

Mbhele described the April fires as "devastating" as she saw the flames encroaching on the university, where she works. She fought the flames for two days, proud and relieved that she was able to help contain the spread.

From teaching people to clear dry twigs from around their homes to building with less wood, Mbhele feels that poorer communities need to be empowered to protect themselves and their environment from fires in the future.

She also called on South Africans to donate their time and money to battle the blazes.

"I once came back from fighting a fire - wet, muddy and tired - and people had donated food, even pizza," Mbhele said.

"It didn't matter that it was cold, I ate it because I was starving. And I loved that moment because I saw how Cape Town got together and we were a community."

After fighting wildfires for 23 years, Grigory Kuksin never expected to stand back and allow one to burn.

But in north Siberia, Kuksin, who heads Greenpeace's Russian firefighting operation, is doing just that: letting vast blazes engulf entire forests.

"We have had to just step back and surrender, sacrificing large areas to the fires," he said.

.gif?language_id=1)

Part of a special force assembled to put out fires in nature reserves, Kuksin criss-crossed the nation this summer to support local firefighters with equipment and know-how.

He is still coming to terms with what he has seen.

In Karelia, a western region close to neighbouring Finland known for its lakes and heavy rainfall during summer, he saw rare peat fires.

"For the first time in my life I saw humid wetlands on fire. It seemed impossible."

Russian meteorologists say temperatures recorded in June and July were 3.9 degrees Celsius higher than the average of the past 20 years, resulting in dozens of wildfires - with some breaking out on islands in one of Europe's largest lakes.

Kuksin, who teaches sports to children with special needs in his spare time, goes for weeks at a time without seeing his wife and son who live on the outskirts of Moscow.

"My work takes a lot of my time away from my family. We are trying to cope with it. My family has never tried talking me out of doing what I do," he said.

If there is one stereotype that volunteer firefighter Katherine Robinson-Williams wants to banish, it is the notion that fighting fires is a man's job.

"Firefighters come from a range of backgrounds. They aren't always men," she said from the Hunter Valley in the Australian state of New South Wales.

Her mother, grandmother and sister-in-law all fight fires, and she expects her baby daughter will become a firefighter, too.

Robinson-Williams is what Australians affectionately call a "firie", one of nearly 200,000 volunteers - about 1% of the population - called on to tackle blazes alongside full-time firefighters.

Longer and more severe wildfire seasons that experts say are prompted by climate change has led to a shortage of volunteers, and Robinson-Williams said more countries could soon have to rely on volunteers.

"There will never be enough firefighters to protect every person's door, every person's caravan, every person's car, every person's farm," said Robinson-Williams, whose day job involves rehabilitating racehorses.

"Sooner or later, everyone else is going to actually have to step up."

Australia's most populous state closed out its quietest fire season in a decade in early 2021, thanks to a cool, wet summer that offered a reprieve from the uncontrolled blazes that torched large swathes of the country in 2019 and 2020.

Robinson-Williams takes scant solace from one cool, wet year as she recalls the horrors of the previous two seasons.

"I have an iron stomach, but some of the things I saw broke me," she said.

Robinson-Williams was 14-weeks pregnant when she joined crews on the ground battling blazes and evacuating towns during Australia's 2019 fires, the worst in decades.

"We were finding deceased animals that were caught in the blaze. We saw remnants of houses, remnants of sheds, cattle with no water troughs because they literally just disintegrated with the heat."

Although family and friends worried how the smoke and heat would affect her pregnancy, Robinson-Williams wore protective gear and had her doctor's approval.

"Most people have this mentality in their heads that women can't do things because they're pregnant, and that's not the case. I knew what my body could take," she said.

"My mum fought fires in '94 and '96 when she was pregnant with me. My grandmother fought fires back in 1970 when she was pregnant with my mum.

"Until there are studies that come out in regards to firefighters and reproductive health, there is no way to know what's safe and what's not."

While battling a blaze last year, Robinson-Williams and her crew were almost crushed by a falling tree. Her quick thinking saved her, but once the adrenaline wore off, she found herself struggling to process what had happened.

"It's not spoken of in firefighting, but there is a psychological impact," she said.

"We're going to get pushed to the absolute brink, and we're just going to collapse. And that time has started to come."

This story is part of a series examining how the lives of firefighters around the world are being impacted by climate change.

Reporters: Kim Harrisberg, Seb Starcevic and Angelina Davydova

Text editing: Tom Finn and Helen Popper

Graphics: Tereza Astilean

Video editing: Amber Milne

Producer: Amber Milne

Video footage courtesy of Greenpeace

From climate change to land rights - the best stories, the biggest ideas, the arguments that matter.

Just 1 email a week - every Monday with our best long reads of the past week!