Battle from below: South African miners fight climate change

BY Kim Harrisberg 17 September 2020

Four nights a week, Given Zuli packs some food, meets his colleagues at the entrance of an abandoned coal mine in South Africa's eastern Mpumalanga province, and descends into the earth for up to 12 hours, chipping away at the black rock.

Zuli is one of thousands of small-scale, illegal miners across South Africa - a number believed to be on the rise as unemployment spikes in a brittle economy - who make a living selling coal collected in abandoned, derelict mine shafts.

But Zuli is also part of a growing environmental movement in the coal-rich province, campaigning for a shift to cleaner energy, away from the black rock that both feeds his two children and pollutes the air they breathe.

As well as the health fears, Zuli and his colleagues worry about their children falling into open mines or tailings dams storing toxic byproducts that miners dub 'Pits of Death'.

At one open mine visited by the Thomson Reuters Foundation, rotting carcasses of about four sheep and cows that had fallen into the pits lay in a heap with the smell of decaying flesh hanging in the air.

"Our everyday lives depend on coal," said Zuli, 32, a qualified public safety officer who formerly worked for a mining company and is well aware of the risks faced by artisanal or informal miners who are killed every year by collapsing rocks.

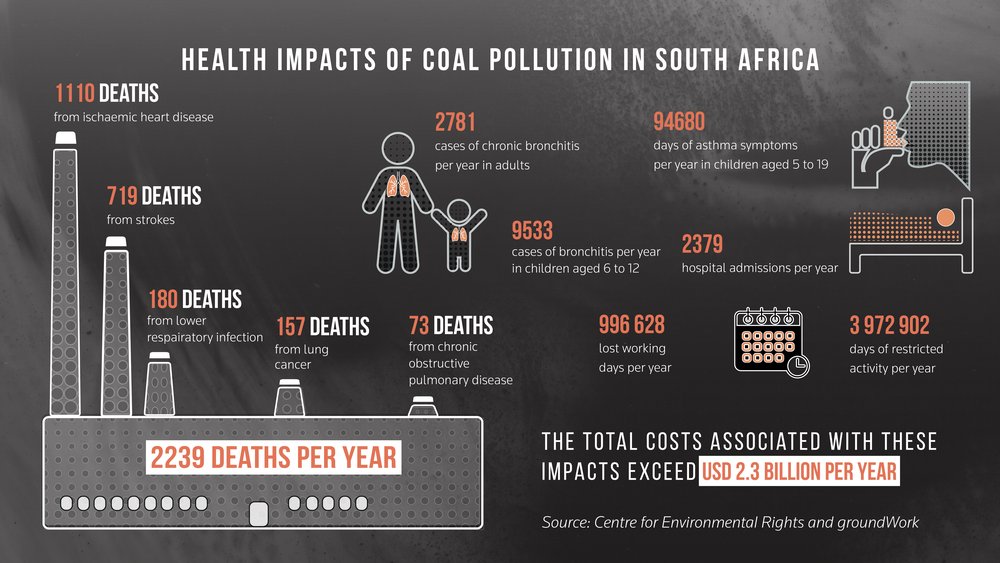

"It pollutes our water, our air. Asthma is a common sickness here. But it also keeps us warm and feeds us," said Zuli, watching a cloud of smoke spreads like ink from a nearby chimney.

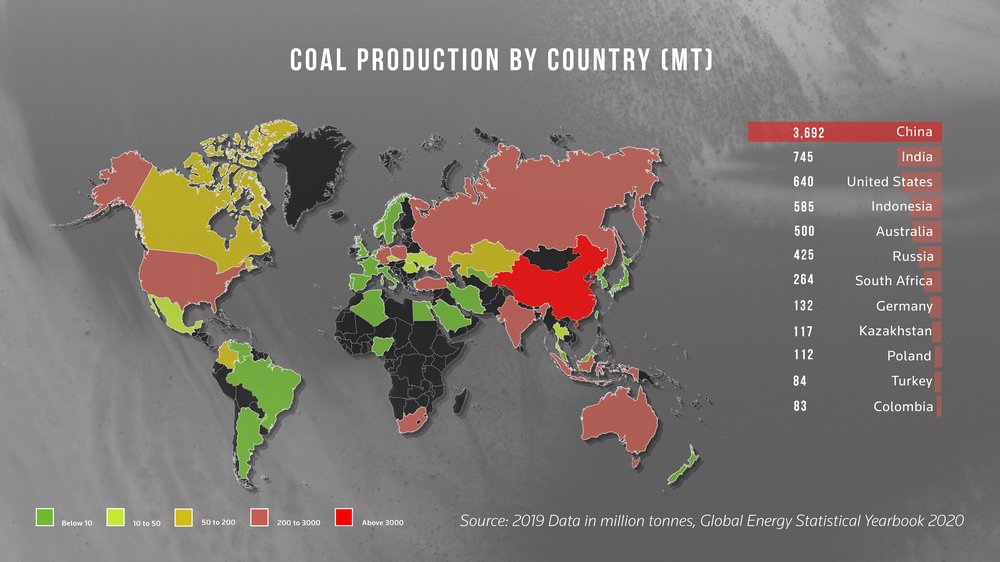

Coal is the main fuel used for power generation in Africa's most industrialised nation of 58 million people, accounting for more than 80% of output, but making South Africa one of the top 20 emitters of carbon dioxide worldwide.

However the sector is important to South Africa, the world's seventh largest coal producer, contributing 2% to the country's gross domestic product in 2017 while employing 92,230 people in a country where 30% of the workforce are jobless.

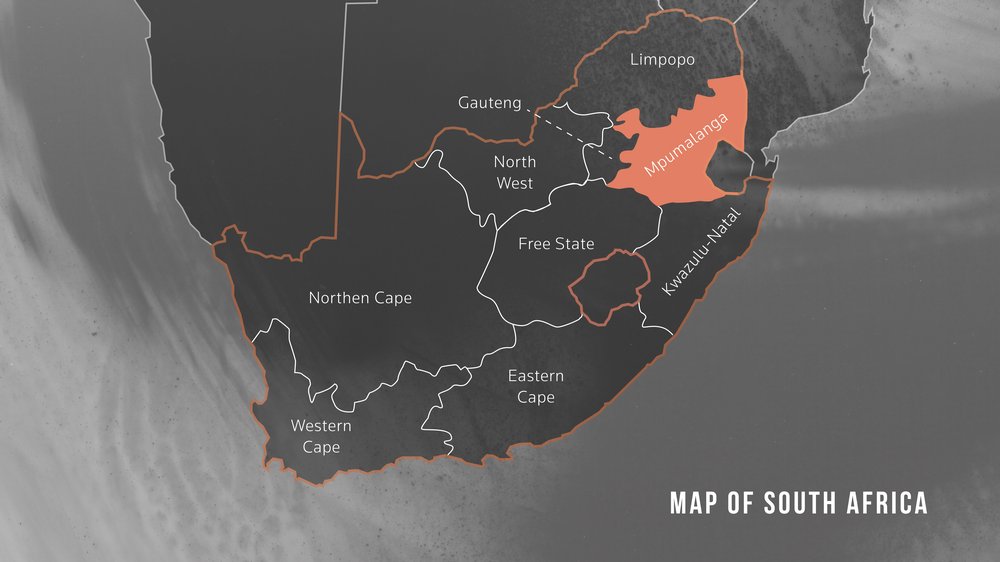

State-run energy provider Eskom employs about 46,000 people and owns 12 coal fire power stations in Mpumalanga, as well as two in Limpopo and one in Free State provinces. It also runs four gas turbine power stations in Western and Eastern Cape.

But the industry is facing major challenges including rising costs, lower investment levels and inadequate water and rail infrastructure, as well as greater environmental requirements.

In August 2019, a Greenpeace-funded study using NASA satellite data found the town of Kriel in Mpumalanga, which has eight coal power stations within a 100 km radius, was the second biggest sulphur dioxide emissions hotspot in the world.

Climate concerns and reluctance by banks to fund coal have forced some larger and international mining companies to either sell their coal assets or to limit their exposure to the fossil fuel in recent years.

But this has also sparked a new generation of smaller mining companies keen to continue extraction.

While Zuli and thousands of others in Mpumalanga depend on abandoned mines to survive, they also want to educate the community about climate change and hope to be a part of the country's transition to cleaner energy.

"Coal gives and it takes away," said Zethu Hlatshwayo, spokesman for Khuthala Environmental Care Group - the eco-rights organisation working with the informal miners to rehabilitate mines and push for clean energy.

"We know the health impact is dire, but all our lives we have known coal as a source of energy, warmth and food," Hlatshwayo told the Thomson Reuters Foundation from his home that he shares with his grandmother in the town of Ermelo.

But Khuthala members want change, as promised by South Africa when it signed the Paris Agreement vowing to reduce its carbon emissions and cut back on its dependency on coal.

"These degraded, open pits could be transformed into solar farms," said Zuli. "And if the transition away from coal involves us, why not?"

An estimated 30 million people are involved in artisanal or small-scale mining globally and 30-40% of this takes place in Africa, according to the African Minerals Development Centre, a mining research centre run by the United Nations in Ethiopia.

In South Africa, without a permit this small-scale mining is illegal and Zuli has been arrested at least 10 times since joining this band of so-called "zama-zamas" in 2014.

Zama-zamas in Zulu translates to "those who try to get something from nothing" and draws throngs of unemployed people from both within South Africa and neighbouring countries trying their hand at mining both coal and gold.

At times, the zama-zamas have been at the source of violent confrontation between authorities and formal miners.

"It is true, we are trying and trying. But we don't like that name," said Zuli. "It carries a lot of stigma. We call ourselves artisanal miners."

According to the most recent census data, Mpumalanga province has a 38% unemployment rate - a big reason Zuli and others risks their lives underground every day.

As a formal miner, Zuli was earning about 3,500 rand ($200) a month. Working for himself, Zuli earns up to 25,000 rand.

"I feel a lot of emotions when I go underground: tired, frustrated, grateful," said Zuli, adding that during the recent coronavirus lockdowns some 1,500 new small-scale miners joined the 3,000 or so already mining Mpumalanga's abandoned shafts.

"Claustrophobia is not something I feel anymore. That word went out a long time ago. It's literally hard to have phobias when you hungry," Zuli said.

But the dangers of going underground hang over him.

About twice a month, rocks collapse in the shafts. Thick wooden poles propped between the underground rooftops and the jagged floor act as indicators of when to run: splitting wood means the roof will soon follow.

"We probably see up to five fatalities a year," said Zuli, who sells most of his coal to town residents for cooking and heating their homes.

"I take a lot of emotions down there with me. My children might lose me. But it's the only option I have. I am working for them to eat."

Aerial shots of Mpumalanga province reveal deep brown and black pockmarks stamped into the earth - the remains left behind from open cast mines - surrounded by green fields and farms.

There are about 6,000 abandoned and derelict mines across the country, according to the Council for Geoscience, one of the National Science Councils of South Africa.

"This is a very, very fertile agricultural area," said Danie du Plessis from the local farmers union the Transvaal Agricultural Union of SA (TAU-SA) peering down at the earth from a plane above.

"Cattle, sheep, maize, soya beans. Anything can grow here."

Knowing this, the Khuthala (meaning tireless workers) Environmental Care Group has worked with artisanal miners and thousands of other community members for the last 20 years to grow food to feed themselves, often alongside these open mines.

During the recent lockdowns, hundreds survived on their own produce.

"We started Khuthala in 2000, when we were hungry and tired of losing family members to the mines," said Hlatshwayo, referring to community members who have died from lung disease or from falling into open mines.

Today Khuthala run workshops on climate change, planting trees, and how to help rehabilitate open mines. The group has set up an organisation for artisanal miners called the National Association of Artisanal Miners.

They have also rehabilitated a 5 hectare dump into a park where their head office is based out of a cabin. Clean spring water is now home to crabs and fish, indigenous trees draw hundreds of bird species, and vegetables crops feed locals.

The eco-group also runs environmental workshops on the property for children under the programme "Operation Catch Them Young" for those who have never seen nature or flowing water.

At the park entrance they run a car wash to provide jobs and every year, the park sees hundreds of activists and community members arrive for the Environmental Justice Festival to discuss topics such as climate change and clean energy.

"We see ourselves as environmental watchdogs," said Hlatshwayo.

But aware of the lifeline that coal mining gives many families, Khuthala organisers have also started talks with the Department of Mineral Resources to legalise informal mining.

"We want to be clear. We 100% support the fight against climate change. We see it in our everyday lives," said Hlatshwayo, who said his lungs burn just from breathing in Ermelo, the mining and agricultural town in Mpumalanga.

But the department said in emailed comments that they will not have a current working relationship with "illegal miners".

The department said it invited anyone interested in working with them to attend their workshops to understand requirements for industry participation.

According to the Centre for Environmental Rights, Eskom's coal-fired stations are responsible for about 2,239 deaths each year caused from heart disease, respiratory infections, lung cancer and strokes.

The Mpumalanga Department of Health did not respond to repeated requests by phone and email for comment.

Despite the risks involved, hungers drives the informal miners underground every day where "blasters" chip away at the coal for hours with pickaxes, filling wheelbarrows and sacks that another miner will heave above ground for collection.

"Must we sit on top of this (coal) and die poor people? The whole world would be laughing at us," said Hlatshwayo.

Khuthala members want to mitigate the risks of living side-by-side to open mines.

South Africa has the highest number of tailings dams globally - embankments used to store toxic byproducts of mining operations - into which the cattle and sometimes children fall.

Khuthala members are building bridges, fences and closing entrances so people can bypass dangerous mines and these tailing dams. They encourage the informal miners to move away from unstable mine shafts that put anyone at risk.

"We need to protect and conserve both the environment and the people who are a part of it," said Hlatshwayo.

According to government's Integrated Resource Plan in October 2019, by 2030 coal will account for 59% of electricity compared to 90% in 2019, with another 8% from hydropower, 6% from solar power, 18% from wind and 1% from gas and diesel.

Currently, solar and wind make up 0.9% each, diesel 1.7% and other energy sources make up 2.4%, excluding natural gas and nuclear, according to the most recent figures.

"Eskom contributes 40% of carbon emission into the country, it's there, we admit it. We are not denialists," Dan Mashigo, a general manager for Eskom, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in an interview in his office in December last year.

"It's the simple fact that we got it, it's in abundance. We still have probably 200 years more years of coal in the ground."

Eskom spokesman Sikonathi Mantshantsha said the public utility recently started accepting proposals from investors on how to turn coal power plants reaching the end of operating life into alternative energy structures like wind turbines.

These new structures would look to employ and set aside shareholding for local residents, said Mantshantsha, although an exact timeline or hard figures are hard to know at this stage.

"Eskom will still mine and burn coal for many years, but we take the transition towards renewable energy very seriously," he said in a phone interview.

Research published in the academic journal Solar Energy said that a transition to cleaner energy could create 200,000 jobs by 2030 and one million more by 2050.

The gradual transition to clean energy, be it wind or solar, is something Khuthala welcomes, but environmental justice needs to co-exist with economic justice, Hlatshwayo said. They want to be one of the 200,000 sooner rather than later.

After 12 hours of chipping away at coal walls with a pick-axe, Zuli climbs back up the steps towards the light with throbbing shoulders and calloused hands to begin his walk home.

He waters his garden and scrubs off the black dust coating his body. This has been his ritual for the past six years and one he is willing to see change.

"If we can move from this way to cleaner energy and we are not left out, if this clean energy could be beneficial to the community at large, then this would be enough."

From climate change to land rights - the best stories, the biggest ideas, the arguments that matter.

Just 1 email a week - every Monday with our best long reads of the past week!